How Early Explorers Created Maps Without Satellites

In today’s digital age, we take highly accurate maps for granted.

With the help of satellites, GPS technology, and advanced imaging systems, we can instantly navigate from one place to another with pinpoint precision. We can even create our very own custom map posters, not for directions on how to navigate anywhere, but for the memory-keeping fun of it!

However, for most of human history, maps were created without the benefit of satellite imagery or modern technology. Instead, early explorers relied on a combination of observation, mathematical calculations, and physical measurement to chart the world around them.

These maps were crucial for travel, trade, and military strategy, often determining the success or failure of entire expeditions.

The process of mapping unknown regions was both a scientific and artistic endeavor. Explorers needed to document coastlines, mountain ranges, rivers, and political boundaries without aerial perspectives, requiring immense skill and ingenuity.

Their efforts shaped the way we understand geography today. Many of the techniques they pioneered remained in use for centuries, laying the foundation for modern cartography.

But how exactly did early explorers create detailed maps without satellites?

They used a variety of tools and methods, from celestial navigation to painstaking land surveys. Some relied on mathematical projections, while others adapted indigenous knowledge passed down through generations.

Their maps, though sometimes flawed or exaggerated, played a critical role in shaping human exploration and commerce.

Let’s explore the fascinating history of early cartography, the tools and techniques used by explorers, and how their maps evolved over time.

We will delve into ancient mapping systems, the role of early scientific instruments, and some of the most famous historical maps.

The Earliest Forms of Mapping

Long before satellites, GPS, and even printed maps, humans needed a way to navigate their surroundings. Mapping has been an essential tool for survival, trade, and exploration since ancient times.

While we often associate maps with paper or parchment, the earliest forms of mapping were carved into stone, painted on cave walls, or etched onto clay tablets.

These primitive maps helped early humans mark hunting grounds, water sources, and territorial boundaries.

Over time, as civilizations grew and explored farther from their homelands, maps became increasingly sophisticated, blending geographic knowledge with artistic representation.

Prehistoric Maps: The First Attempts at Cartography

One of the oldest known maps dates back nearly 14,000 years. Found in the caves of Lascaux, France in 2021, this ancient drawing— known as the Saint-Bélec Slab— is believed to depict the surrounding landscape, complete with mountains, rivers, and possibly even stars.

Similarly, prehistoric rock carvings found in Turkey and Italy suggest that early humans attempted to create rudimentary maps to navigate their environment. These early depictions, though lacking in precision, reflect humanity’s innate desire to document and understand the world.

As societies evolved, so did their mapping techniques.

The Babylonians, for instance, created some of the first known geographic maps on clay tablets around 2300 BCE. These maps were not just for navigation; they also reflected spiritual and mythological beliefs, often placing the homeland at the center of the known world.

The Babylonian Imago Mundi, a circular world map from the 6th century BCE, depicted the world as a flat disk surrounded by a cosmic ocean. While geographically inaccurate by modern standards, it was a major step toward organized cartography.

Ancient Civilizations and Their Contributions to Mapping

Egyptians, Greeks, and Chinese civilizations made significant advances in cartography.

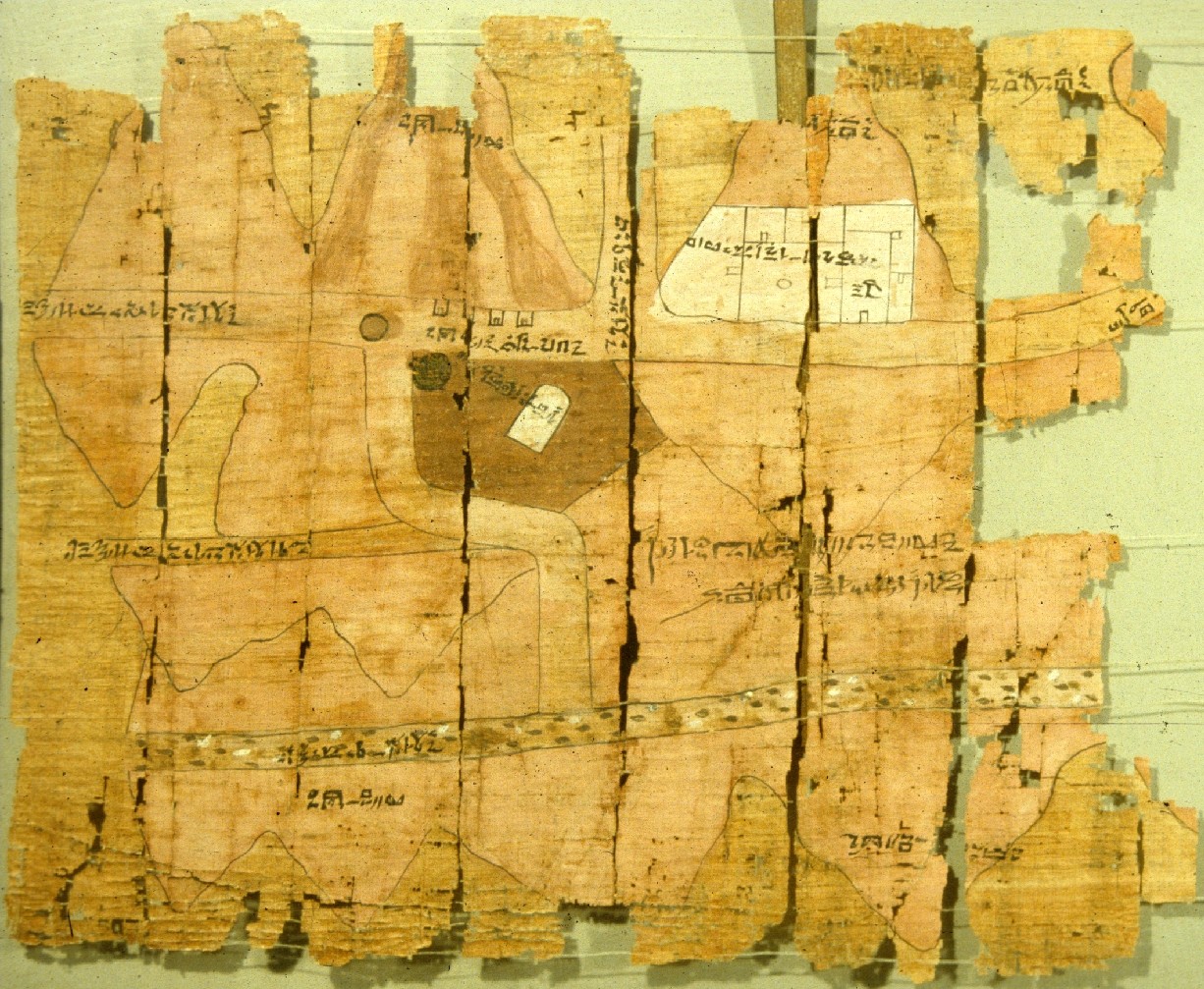

The Egyptians, for example, developed highly detailed maps for land surveying, particularly useful for redistributing land along the Nile after annual floods.

One of the earliest surviving maps, the Turin Papyrus Map (c. 1150 BCE), is an Egyptian document showing gold mines and quarry locations, highlighting the practical use of maps for resource management.

The Greeks took mapping a step further by introducing mathematical concepts to geography.

Around 500 BCE, the philosopher Anaximander is believed to have created one of the first world maps in the Greek tradition. While his original work does not survive, later Greek maps, influenced by his ideas, attempted to depict the known world in a logical, proportionate manner.

By the time of Ptolemy (2nd century CE), cartography had become a highly mathematical discipline. Ptolemy’s Geographia introduced the idea of latitude and longitude, which laid the groundwork for later European maps.

Meanwhile, in China, early maps were used extensively for governance, military planning, and trade. Chinese cartographers developed sophisticated mapping techniques centuries before their European counterparts.

The Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) saw the rise of grid-based maps that measured distances accurately using a standard scale.

In 1137 CE, a Chinese polymath named Shen Kuo even described how to use a magnetic compass for navigation, a major breakthrough in cartography.

The Role of Astronomy and Geometry in Early Cartography

Many ancient maps were based on celestial observations. Early civilizations recognized that the position of the sun, moon, and stars could be used to determine direction.

The Polynesians, for instance, became master navigators by relying on the stars to guide their voyages across vast oceans. Their maps, often made of sticks and shells, represented ocean currents and island positions rather than landmasses in the way Western maps did.

Greek mathematicians like Eratosthenes (c. 276–194 BCE) further advanced cartography by calculating the Earth’s circumference with remarkable accuracy.

His work suggested that the Earth was a sphere and that distances between locations could be measured mathematically.

While this knowledge was lost to much of medieval Europe, it persisted in the Islamic world, where scholars continued refining Ptolemaic maps and improving upon existing geographic knowledge.

The earliest forms of mapping were a mix of art, science, and mythology. Though primitive compared to modern maps, these early attempts helped civilizations navigate, govern, and expand their influence.

The combination of observation, geometry, and astronomical calculations set the foundation for the more advanced maps that explorers would later use to chart the world.

Tools and Techniques Used by Early Explorers

Before satellites, early explorers had to rely on a variety of tools and techniques to map their surroundings.

These methods were often imprecise by modern standards, but they represented the best available technology of their time.

Explorers had to measure distances, determine directions, and estimate locations—all without aerial views or electronic aids. Instead, they turned to mathematical calculations, celestial navigation, and physical surveying to create maps that shaped the world.

Compasses and Astrolabes: Navigating by Magnetic Fields and Stars

One of the most revolutionary tools in early navigation and mapping was the magnetic compass.

Although the Chinese first developed the compass as early as the 2nd century BCE, it wasn’t widely used for navigation in Europe until the 12th century.

The compass allowed sailors to determine direction even when landmarks were not visible. This was especially crucial for oceanic exploration, where visual references were often unavailable.

While the compass provided direction, explorers needed another tool to determine their latitude: the astrolabe.

The astrolabe, which originated in ancient Greece and was later refined by Islamic scholars, allowed navigators to measure the angle of celestial bodies above the horizon.

By calculating the sun’s position at noon or measuring the height of the North Star, sailors could estimate their location relative to the equator. Though it was not precise enough to determine longitude, it was a major advancement in maritime navigation.

Dead Reckoning: Estimating Position Without Landmarks

One of the most common techniques used by early navigators was dead reckoning. This method involved estimating one’s current position based on previously known locations, speed, direction, and time traveled.

Sailors would track their speed using a log and line—a rope with knots spaced at regular intervals. By counting how many knots passed through their hands in a given time period, they could estimate speed and, in turn, distance traveled.

However, dead reckoning was highly prone to errors. Small mistakes in speed estimation, currents, or wind direction could lead to significant deviations over long journeys.

Despite its limitations, it remained a key technique for centuries, especially in open-sea voyages.

Land Surveying: Measuring the Land with Chains and Rods

For mapping land rather than oceans, early explorers used land surveying techniques. This method involved measuring distances and angles between fixed points using chains, rods, and other simple instruments.

One of the earliest known surveying tools was the Gunter’s chain, a 66-foot-long metal chain used for measuring land plots with remarkable consistency.

Surveyors would take measurements from multiple locations and use basic geometry to create an accurate representation of the terrain.

This process, known as triangulation, involved selecting a baseline and measuring angles from both ends to distant landmarks. By using trigonometric calculations, cartographers could determine distances and create highly detailed maps.

Triangulation: A Breakthrough in Accurate Mapping

One of the most effective techniques for improving the accuracy of maps was triangulation, which became widely used in the 17th century.

By selecting two fixed points (such as mountain peaks or tall towers) and measuring the angles to a third location, explorers could calculate distances with remarkable precision.

This method allowed for the creation of more proportional and reliable maps, particularly in land-based cartography.

Triangulation was first formalized by the Dutch mathematician Willebrord Snellius in the early 17th century and later became the standard method for national surveys.

It remained a cornerstone of cartography well into the 20th century.

Celestial Navigation: Using the Stars as a Guide

Before GPS, celestial navigation was the most reliable way to determine location on long voyages. This technique involved using the sun, moon, and stars to estimate latitude and, eventually, longitude.

Early explorers relied heavily on the North Star (Polaris) in the Northern Hemisphere, as its position in the sky changes predictably based on latitude.

The development of more advanced instruments, such as the sextant in the 18th century, greatly improved the accuracy of celestial navigation.

The sextant replaced the astrolabe and allowed for more precise measurements of celestial angles, reducing navigational errors.

By the time of Captain James Cook’s voyages in the late 18th century, celestial navigation had reached a level of accuracy that enabled explorers to map coastlines and islands with an unprecedented degree of detail.

The tools and techniques used by early explorers were ingenious solutions to the challenges of navigation and mapping without modern technology.

Though compasses, astrolabes, dead reckoning, and land surveying were often imprecise, they laid the foundation for centuries of exploration and discovery.

With the refinement of methods like triangulation and celestial navigation, maps became increasingly accurate, helping to connect distant parts of the world.

Famous Early Maps and Their Creators

Throughout history, maps have been more than just tools for navigation—they have shaped human understanding of the world, influenced exploration, and even determined the fate of entire nations.

The earliest maps were often filled with mythological creatures, vast uncharted territories, and sometimes, deliberate distortions based on religious or political beliefs.

However, as explorers gathered more knowledge, maps became increasingly accurate. Several cartographers and explorers made lasting contributions to the field of cartography, creating maps that pushed the boundaries of known geography.

Claudius Ptolemy’s Geographia: The Foundation of Western Cartography

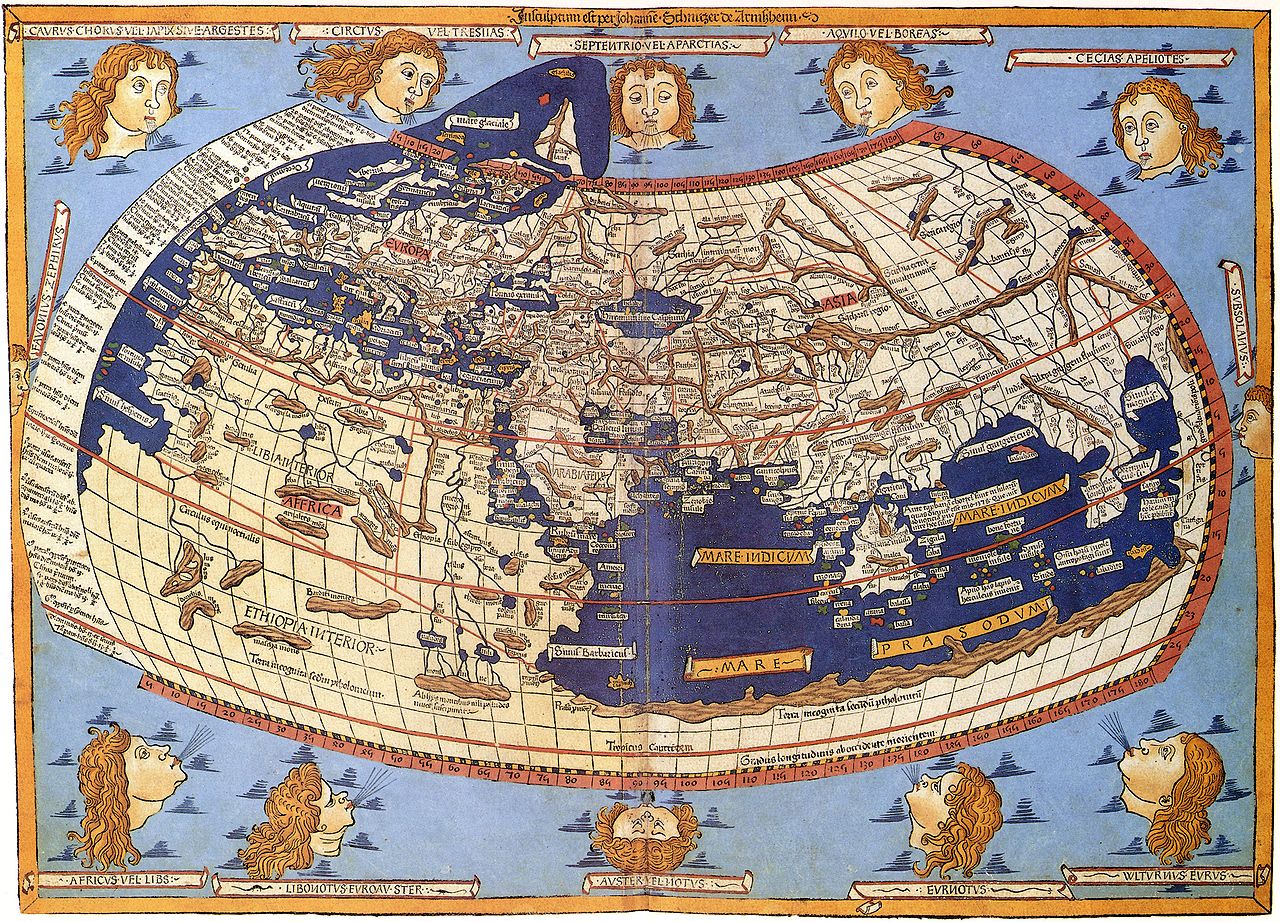

One of the most influential figures in early cartography was Claudius Ptolemy, a Greek mathematician, geographer, and astronomer who lived in the 2nd century CE.

His work, Geographia, was a monumental effort to create a systematic approach to mapping the known world.

Ptolemy’s maps, though not entirely accurate, introduced key concepts such as latitude and longitude, providing a mathematical basis for cartography.

He also proposed a projection method for displaying the curved surface of the Earth on a flat map—an idea that would later influence Renaissance-era cartographers.

While his original maps have been lost, medieval scholars preserved and copied his work, ensuring that his influence lasted for centuries.

His geographic theories remained dominant until the Age of Exploration, despite some inaccuracies—such as underestimating the Earth’s circumference.

The Mappa Mundi: Medieval European World Maps

During the Middle Ages, many European maps were based on religious beliefs rather than scientific observation.

The Mappa Mundi (Latin for "map of the world") was a common medieval style of cartography that placed Jerusalem at the center of the world and often depicted biblical events alongside real geography.

One of the most famous surviving examples is the Hereford Mappa Mundi (c. 1300 CE), a massive circular map that blends theology with geography.

Unlike modern maps, it was not designed for navigation but as a visual representation of a Christian worldview.

Europe, Asia, and Africa were depicted, but with significant distortions and inaccuracies, as medieval cartographers had little firsthand knowledge of distant lands.

The Portolan Charts: Early Nautical Maps

As maritime exploration expanded in the late Middle Ages, the need for practical navigation maps increased.

Portolan charts, which emerged around the 13th century, were some of the first detailed and accurate nautical maps. Unlike earlier European maps, which were largely symbolic, portolan charts were based on actual observations of coastlines and harbors.

These maps featured a network of rhumb lines, which indicated consistent compass directions, allowing sailors to navigate more effectively.

Created by skilled Italian, Catalan, and Portuguese cartographers, portolan charts were instrumental in the rise of European sea trade and exploration. They helped merchants and explorers traverse the Mediterranean, the Atlantic coast of Europe, and eventually, the wider world.

Martin Waldseemüller’s 1507 Map: The First Use of “America”

One of the most groundbreaking maps in history was created by the German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller in 1507.

This map was the first to use the name “America” in honor of the explorer Amerigo Vespucci, who had argued that the newly discovered lands were not part of Asia but a separate continent.

Waldseemüller’s map was revolutionary because it depicted the Atlantic Ocean more accurately than earlier maps and suggested that the New World was distinct from Asia.

This recognition of a separate continent marked a significant shift in European understanding of global geography.

James Cook’s Pacific Maps: Precision Mapping Through Observation

By the 18th century, maps had become increasingly sophisticated, thanks in part to the work of Captain James Cook.

During his voyages across the Pacific, Cook meticulously mapped coastlines with unprecedented accuracy. His maps of Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific Islands were so precise that they remained in use for decades.

Cook relied on advanced celestial navigation techniques and used the newly developed marine chronometer to determine longitude more accurately than any explorer before him.

His maps helped expand European knowledge of the Pacific region and facilitated further exploration and colonization.

The evolution of cartography was driven by a mix of scientific discovery, exploration, and artistic interpretation. From Ptolemy’s mathematical models to the practical navigation charts of the Age of Exploration, maps gradually became more accurate and reliable.

Each breakthrough in cartography brought humanity closer to understanding the true shape of the world. However, despite these advancements, early explorers still faced significant challenges in mapping unknown territories.

The Role of Exploration in Mapmaking

Maps and exploration have always been deeply intertwined. Every major leap in cartography has been fueled by daring adventurers pushing the boundaries of the known world.

Without satellites, early explorers had to rely on direct observation, rough sketches, and primitive measuring tools to record their journeys.

Their discoveries shaped the maps of their time and allowed future generations to navigate and expand into new lands.

From the ancient Silk Road to the uncharted waters of the Pacific, explorers played a critical role in the development of accurate geography.

How Explorers Expanded the World Map

In the early days of cartography, maps were limited to the knowledge of the time. Areas beyond familiar trade routes were often left blank, labeled with speculative names, or filled with mythical creatures. It was only through exploration that the world map began to take shape.

- Marco Polo (1254–1324): One of the most famous travelers in history, Marco Polo journeyed from Venice to China and recorded his observations in The Travels of Marco Polo. While he did not create maps himself, his detailed descriptions of Asia helped European cartographers update their maps and inspired further exploration.

- Zheng He (1371–1433): A Chinese admiral of the Ming Dynasty, Zheng He led massive naval expeditions across the Indian Ocean, reaching as far as Africa and the Middle East. His voyages contributed to Chinese mapmaking and helped spread knowledge of foreign lands.

- Christopher Columbus (1451–1506): Though Columbus mistakenly believed he had found a new route to Asia, his voyages led to the first detailed European maps of the Caribbean and the Americas. His discoveries reshaped global trade and exploration.

- Ferdinand Magellan (1480–1521): Magellan’s expedition was the first to circumnavigate the globe, proving that the Earth was round and providing invaluable cartographic data on the Pacific Ocean.

- James Cook (1728–1779): As one of the most skilled navigators of his time, Cook’s voyages provided the first accurate maps of Australia, New Zealand, and many Pacific islands. His contributions to cartography were among the most precise of any early explorer.

Indigenous Knowledge and Its Influence on Mapping

While European explorers contributed significantly to mapmaking, indigenous communities had their own methods of navigation and mapping long before outsiders arrived.

Many early explorers relied on indigenous knowledge to guide them through unfamiliar landscapes.

- Polynesians used star charts and wave patterns to navigate vast ocean distances without compasses or written maps. Their stick charts, made of wood and shells, depicted ocean currents and island positions.

- Native American tribes created detailed mental maps of their territories, which were later recorded by European settlers. Some indigenous maps, drawn on bark or animal hides, depicted trade routes, rivers, and hunting grounds.

- African and Middle Eastern traders had extensive knowledge of desert routes long before European explorers arrived. The trans-Saharan trade networks were mapped through oral tradition and physical landmarks rather than written maps.

The Impact of the Age of Exploration on Mapmaking

The 15th to 17th centuries marked a turning point in cartography. The Age of Exploration led to an explosion of new maps as European nations sought to document and claim new territories.

- The Portuguese and Spanish Empires: Portugal and Spain led the charge in global exploration, producing some of the most detailed maps of the New World and Africa. The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) even used maps to divide the world between Spain and Portugal.

- The Dutch and British Empires: The Dutch became pioneers in commercial cartography, producing some of the most accurate maritime maps of the time. The British, particularly during the 18th and 19th centuries, used detailed surveying techniques to map vast regions of Asia and Africa.

- Advances in Longitude Measurement: Before the 18th century, determining longitude was one of the greatest challenges in cartography. The development of the marine chronometer, a precise timekeeping device, allowed explorers like James Cook to map coastlines with extraordinary accuracy.

Explorers as Mapmakers: A Dual Role

Many explorers were not just travelers but also cartographers. They meticulously recorded their routes, measured distances, and sketched coastlines. Some even developed their own mapping techniques:

- Samuel de Champlain, the French explorer known as the "Father of New France," personally created maps of Canada’s Atlantic coast and the Great Lakes region.

- Lewis and Clark, commissioned by Thomas Jefferson, mapped vast portions of the western United States, detailing rivers, mountains, and indigenous settlements.

- David Livingstone, an explorer of Africa, provided crucial information about the Zambezi River and the interior of the continent, which was later used in colonial maps.

The work of early explorers fundamentally changed cartography. By venturing into the unknown, they transformed vague and often mythical maps into practical navigation tools.

Their observations, combined with indigenous knowledge, created a more complete picture of the world.

However, early maps were still prone to inaccuracies and misconceptions.

Challenges and Errors in Early Maps

Despite the remarkable ingenuity of early explorers and cartographers, their maps were often riddled with inaccuracies, distortions, and outright fabrications.

Without the benefit of aerial surveys or satellite imagery, early mapmakers relied on firsthand accounts, rough measurements, and sometimes pure speculation to chart the world.

While their efforts laid the foundation for modern geography, early maps often reflected the limitations of their time—both in terms of technology and cultural biases.

Distortions and Myths: When Maps Contained More Fantasy Than Fact

Many early maps were based on incomplete knowledge, leading to exaggerated or entirely fictional depictions of the world. Some of the most common distortions included:

- Sea Monsters and Mythical Beasts: Medieval maps often depicted sea monsters, dragons, and other fantastical creatures in uncharted waters. These additions were sometimes meant as warnings to sailors but were also used to fill in gaps where knowledge was lacking. The 16th-century Carta Marina by Olaus Magnus is a prime example of this, featuring elaborate drawings of sea serpents and giant squid.

- The Island That Didn’t Exist: Several islands appeared on maps for centuries despite never having existed. One famous example is Hy-Brasil, a mythical island supposedly located west of Ireland. It was included on maps as late as the 18th century before being dismissed as a cartographic error.

- The "Unknown Southern Continent": Early European maps often depicted a massive, unexplored landmass in the Southern Hemisphere, labeled as Terra Australis Incognita. This hypothetical continent was assumed to exist for balance based on Aristotelian symmetry theories rather than any actual exploration. While Antarctica was eventually discovered, early maps wildly exaggerated its size and shape.

- California as an Island: One of the most famous mapping errors in history was the depiction of California as a separate island. Spanish explorers misinterpreted coastal geography in the 16th century, and for nearly 200 years, European maps showed California floating off the coast of North America.

The Longitude Problem: A Major Navigational Challenge

One of the most significant errors in early maps stemmed from the difficulty of measuring longitude.

While latitude could be determined relatively easily using the position of the sun or stars, longitude required precise timekeeping—a technology that did not exist until the 18th century.

Early explorers estimated longitude based on dead reckoning, often leading to massive discrepancies between actual and recorded locations.

This inaccuracy had serious consequences: ships frequently miscalculated their positions, leading to shipwrecks, misnavigation, and territorial disputes.

The problem was finally solved with the invention of the marine chronometer by John Harrison in the mid-18th century.

This highly accurate timepiece allowed sailors to compare the local time (determined by the sun) with the time at a fixed reference point (such as Greenwich, England), providing an accurate longitude calculation.

This breakthrough revolutionized cartography and navigation, leading to far more precise maps.

Political and Religious Influences on Maps

Maps have never been purely objective representations of geography. Throughout history, they have been shaped by political, religious, and ideological influences.

- Eurocentrism and Colonial Bias: Many European maps of the 16th to 19th centuries exaggerated the size and importance of European territories while diminishing or misrepresenting other regions. For example, Africa was often depicted as much smaller than it actually is, reinforcing colonial perspectives.

- Religious Symbolism in Medieval Maps: Christian medieval maps, such as the T-O maps, placed Jerusalem at the center of the world, with Europe, Asia, and Africa arranged around it. These maps were less concerned with geographic accuracy and more focused on religious interpretation.

- Deliberate Cartographic Manipulation: Governments and empires sometimes used maps to assert control over disputed territories. For example, maps created by the British Empire often emphasized their claimed territories, while downplaying indigenous lands and borders.

The Struggles of Mapping Unknown Lands

Explorers faced numerous obstacles when trying to map new regions, including:

- Dense Forests and Impassable Terrain: Mapping land regions was often more difficult than mapping coastlines. Thick jungles, mountains, and deserts made it nearly impossible for explorers to take accurate measurements.

- Unreliable Local Reports: Many early maps were based on secondhand accounts rather than direct observation. Travelers, merchants, and indigenous guides provided valuable information, but their descriptions were sometimes exaggerated, misunderstood, or lost in translation.

- Weather and Environmental Challenges: Explorers often had to contend with extreme weather conditions that made mapping dangerous. Storms, fog, and rough seas could throw off navigation, leading to inaccurate measurements.

Despite their many flaws, early maps were a testament to human perseverance and curiosity. Even with limited tools and knowledge, early cartographers managed to create maps that guided explorers across vast distances.

While errors and distortions were common, each new map brought the world closer to accuracy.

The Transition to Modern Cartography

The evolution of mapmaking was a slow and painstaking process, shaped by centuries of exploration, scientific breakthroughs, and technological advancements.

While early maps were often riddled with inaccuracies and imaginative depictions, the refinement of mathematical techniques, the invention of new tools, and the growing demand for accurate geographical representation gradually transformed cartography into a precise science.

From the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution, mapmaking saw remarkable improvements.

The development of projection techniques, advancements in measuring longitude, and the use of aerial photography all contributed to the transition from the crude maps of early explorers to the precise, detailed maps we use today.

The Development of the Mercator Projection: A Game-Changer for Navigation

One of the most significant breakthroughs in cartography came in 1569 when the Flemish geographer Gerardus Mercator introduced his famous Mercator projection.

Before this, maps struggled to accurately represent the curved surface of the Earth on a flat plane. Mercator’s solution was a cylindrical projection that preserved angles, making it incredibly useful for navigation.

- The Mercator projection allowed sailors to chart straight-line courses across vast oceans without constant recalibration.

- It became the standard for maritime navigation, especially during the Age of Exploration.

- However, it had distortions—landmasses near the poles appeared much larger than they were in reality. For example, Greenland looks as large as Africa on a Mercator map, though Africa is 14 times bigger.

Despite its distortions, the Mercator projection revolutionized mapping, and its influence can still be seen in modern cartography.

Solving the Longitude Problem: The Marine Chronometer

For centuries, longitude remained the greatest challenge in navigation. Explorers could determine latitude using celestial navigation, but pinpointing longitude required accurate timekeeping—a problem that went unsolved for much of human history.

The breakthrough came in the 18th century with the invention of the marine chronometer by John Harrison.

His timekeeping device allowed sailors to compare the local time (determined by the sun’s position) with a fixed reference time, such as Greenwich Mean Time.

The difference between the two times enabled them to calculate their precise longitude at sea.

- The adoption of the marine chronometer significantly improved the accuracy of nautical maps.

- It reduced the number of shipwrecks caused by navigational errors.

- Combined with the Mercator projection, it allowed for the creation of some of the most detailed and reliable maps in history.

With the ability to accurately determine both latitude and longitude, explorers could now map coastlines and continents with far greater precision.

The Rise of National Mapping Surveys

As technology advanced, governments began investing in large-scale mapping projects to establish official geographic records.

- The Ordnance Survey (UK): In the late 18th century, Britain launched the Ordnance Survey, a detailed mapping project initially intended for military defense. These maps became the basis for modern topographic cartography.

- The French Cassini Maps: France undertook one of the earliest attempts at nationwide mapping with the Cassini family’s detailed surveys, which used triangulation to create highly accurate maps.

- The United States Geological Survey (USGS): In the 19th century, the US government commissioned detailed surveys to map the American frontier, facilitating westward expansion.

These national surveys used a technique called triangulation, in which cartographers measured distances and angles between fixed points to create a grid-like representation of the land. This approach greatly improved accuracy compared to earlier methods of estimation.

Aerial Photography and Early Remote Sensing

While early cartographers relied on ground surveys and mathematical calculations, the advent of aerial photography in the 20th century revolutionized mapmaking.

- During World War I and II, aerial reconnaissance became an essential tool for military strategy. Planes equipped with cameras captured high-altitude photographs, which were then used to create detailed maps of battlefields and terrain.

- In the postwar era, aerial photography allowed for rapid mapping of large areas, significantly reducing the time required to produce accurate maps.

By the mid-20th century, cartography had reached a level of accuracy unimaginable to early explorers.

However, the biggest transformation was yet to come: the introduction of satellites and digital mapping, which would make paper maps almost obsolete.

The transition to modern cartography was a long and gradual process, spanning centuries of scientific discovery and exploration.

From the introduction of the Mercator projection to the invention of the marine chronometer and the rise of aerial photography, each advancement brought maps closer to the highly detailed and accurate representations we rely on today.

While modern GPS and satellite imagery have revolutionized mapmaking, the legacy of early cartographers remains deeply embedded in how we perceive and navigate the world.'

How Early Explorers Created Maps: A Final Salute

The ability to create maps without satellites was indisputably one of humanity’s greatest achievements.

Early explorers, cartographers, and navigators worked tirelessly to chart the world using only the tools and knowledge available to them. Their efforts laid the groundwork for modern mapping technology and changed the course of human history.

While today’s maps are created with pinpoint accuracy using satellites and GPS, the ingenuity of early cartographers continues to inspire.

Understanding how maps were made before modern technology helps us appreciate the incredible journey from rudimentary sketches to the highly detailed digital maps we now carry in our pockets.

In the end, the quest to map the world is a testament to humanity’s curiosity and determination—an ongoing endeavor that has shaped civilization and will continue to do so in the future.