The Soviet Union’s Secret Maps: How the USSR Created the Most Detailed Maps of the World

In 1993, just two years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, a British geographer stumbled across a dusty cache of maps in a Latvian bookstore. It became immediately clear that these weren’t ordinary old maps prints.

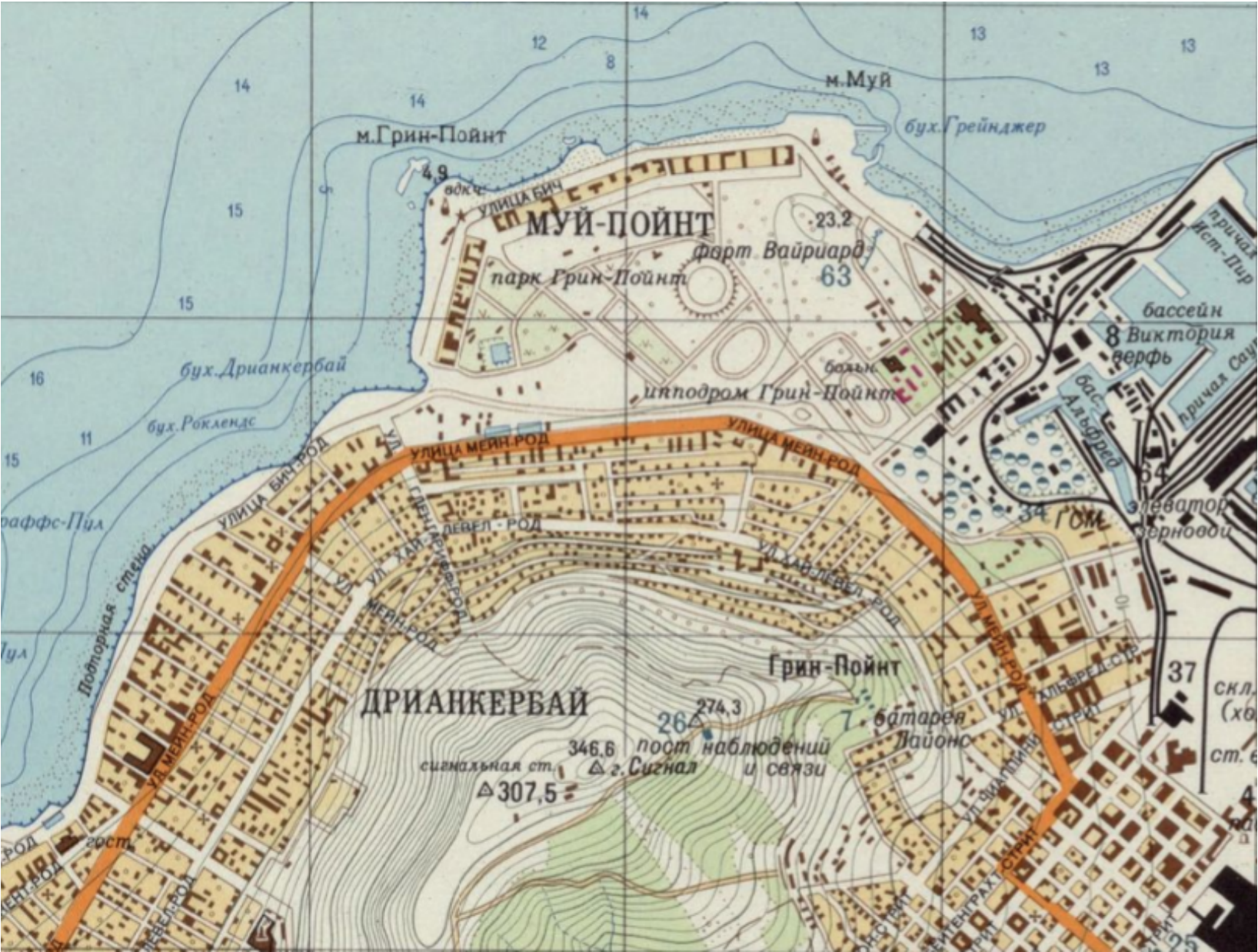

They showed small towns in Kansas, rural roads in Tanzania, and hidden bridges in Britain—complete with load capacities, construction materials, and building functions. More astonishingly, these maps were often more accurate than the best Western military maps of the time.

For decades, in complete secrecy, the Soviet Union had been meticulously mapping not just its own vast territory, but the entire world.

With stunning detail and far-reaching implications, these Soviet maps—a massive project that remains one of the most ambitious mapping endeavors in human history— were not just tools of navigation but instruments of power, espionage, and geopolitical intent.

A Cartographic Power Play: The Cold War Context

To understand why the Soviet Union invested so heavily in global mapping, we need to consider the Cold War as not just a geopolitical rivalry but a psychological and informational arms race.

In the wake of World War II, the world had divided into two major camps: the capitalist West, led by the United States, and the communist East, dominated by the Soviet Union.

While nuclear arsenals and proxy wars dominated headlines, intelligence gathering was the quiet, invisible backbone of national security—and geography was at the heart of it.

The Cold War era ushered in an unprecedented global rivalry where every piece of data had strategic weight, and no form of knowledge was as vital—or as weaponizable—as geographic intelligence.

To the Soviet Union, mapping was not just about geography; it was about control, influence, and preparation for every conceivable scenario—from global war to ideological expansion.

Following the devastation of World War II, Soviet military thinkers came to view geography as one of the most critical theaters of competition. Every tank maneuver, airstrike, missile launch, or invasion plan required precise logistical planning.

And in a country as vast and diverse as the USSR—spanning over 11 time zones—topography, weather patterns, and infrastructure weren’t just academic—they were existential. If a country couldn't master its own terrain, how could it hope to project power abroad?

Moreover, the early stages of the Cold War witnessed a significant asymmetry in technological resources. The Soviet Union did not enjoy the same access to international mapping data as Western nations, whose commercial cartographic industries had been active for decades. Instead of accepting that gap, Soviet leadership chose to erase it—through a tightly orchestrated internal effort that viewed mapping as a form of statecraft.

This philosophy extended outward.

Soviet leaders assumed that future conflicts could erupt anywhere, at any time. Whether in the jungles of Central America, the deserts of North Africa, or the fjords of Scandinavia, the Red Army had to be ready. This was not mere paranoia—it was doctrine.

Soviet military strategy emphasized what was known as “the theater of military operations,” meaning that detailed knowledge of the terrain—any terrain—was essential for troop deployments, missile targeting, and logistical planning.

Crucially, this view of mapping as a military act was embedded within the USSR’s ideological framework. Marxist-Leninist doctrine emphasized central planning and state knowledge of all material resources. Maps were not optional—they were part of the machinery of state control. Every field, factory, and bridge had to be accounted for, whether at home or abroad.

In this sense, the Soviet mapping project became an emblem of the Cold War itself: a competition to know more, to see farther, and to predict what the enemy might do next.

Their cartographic efforts were a reflection of both fear and ambition: fear of capitalist encirclement, and ambition to become the world’s most powerful and informed state.

Inside the Soviet Mapping Machine

The sheer size and organizational complexity of the Soviet mapping apparatus defies easy comparison.

If the CIA was the eyes and ears of the United States, then the General Staff’s mapping department—under the Main Administration of Geodesy and Cartography (GUGK)—was the eyes, ears, and nervous system of the Soviet military-industrial complex.

GUGK functioned as both the operational and intellectual center of Soviet cartography. Located in Moscow, its influence extended through a network of regional offices, military units, research institutes, and production facilities. It oversaw everything from high-level geodetic calculations to the printing presses that churned out map sheets in secure, classified batches.

At its height, the Soviet mapping program employed more than 40,000 individuals. These included:

- Topographers, who conducted ground surveys across the USSR and occasionally abroad under the guise of scientific or diplomatic missions.

- Geodesists, who calculated the exact curvature of the Earth and corrected for geospatial distortions.

- Cartographic editors, who managed symbology, labeling, and design consistency.

- Printing technicians, who worked in secure facilities using high-resolution presses and military-grade inks to produce physically durable maps.

- Data analysts, often working with raw intelligence gathered by GRU agents (military intelligence) and KGB operatives abroad.

One of the program’s most ambitious undertakings was the construction of a uniform geodetic control network—a grid of reference points that spanned the USSR and extended into foreign territories. These points were essential for ensuring that maps aligned perfectly regardless of location or scale.

The Soviets even developed their own unique projection systems, such as the SK-42 coordinate system, which allowed them to represent terrain with minimal distortion for their strategic needs.

The work was methodical and deeply hierarchical.

At its peak, the GUGK employed tens of thousands of individuals, from surveyors and geodesists to illustrators, typographers, and military analysts. These were not just mapmakers—they were engineers of information. The mapping process involved multiple steps:

- Data Collection: Teams gathered data through military reconnaissance, space-based imagery, informant reports, public documents, and more.

- Verification & Cross-Referencing: Information from diverse sources was cross-checked to ensure accuracy.

- Symbolization: Soviet maps used their own symbology system, which was far more extensive and standardized than Western systems.

- Production & Printing: Maps were printed in secret facilities, often in limited runs. Each copy was serialized and tracked.

- Distribution & Control: Only high-ranking military or intelligence personnel could access certain maps. Possession by civilians was criminalized.

The GUGK’s reach was so comprehensive that they produced multiple scales for each region:

- 1:1,000,000 – Strategic overview

- 1:200,000 to 1:500,000 – Operational planning

- 1:100,000 to 1:25,000 – Tactical detail

- 1:10,000 and below – City-scale, block-by-block intelligence

For any given area, multiple drafts of a map would be produced, reviewed, annotated, and compared to other data sources. Field surveys were cross-referenced with aerial photography and satellite images. A city might be redrawn a dozen times to incorporate new intelligence.

Additionally, the Soviets had a strong aversion to relying on foreign-produced data. Even when international mapping sources were available, GUGK revalidated everything internally. The aim was total self-sufficiency in geographical knowledge, ensuring that no outside party could deceive or mislead Soviet planners.

All of this came at an enormous cost—financial, logistical, and human. But for Soviet leaders, the cost was worth it. They believed that the ability to navigate the globe with supreme confidence was a cornerstone of global supremacy.

To maintain secrecy, the USSR also deliberately altered or degraded publicly released maps. Civilian maps omitted whole cities or placed them inaccurately.

For instance, nuclear or industrial towns (like Chelyabinsk-40 or Arzamas-16) were entirely absent from civilian maps, and rivers or roads were sometimes shifted by several kilometers.

This created a strange dual-reality in Soviet cartography: one world for the public, and another, far more detailed world reserved for those in power.

Mapping the Enemy

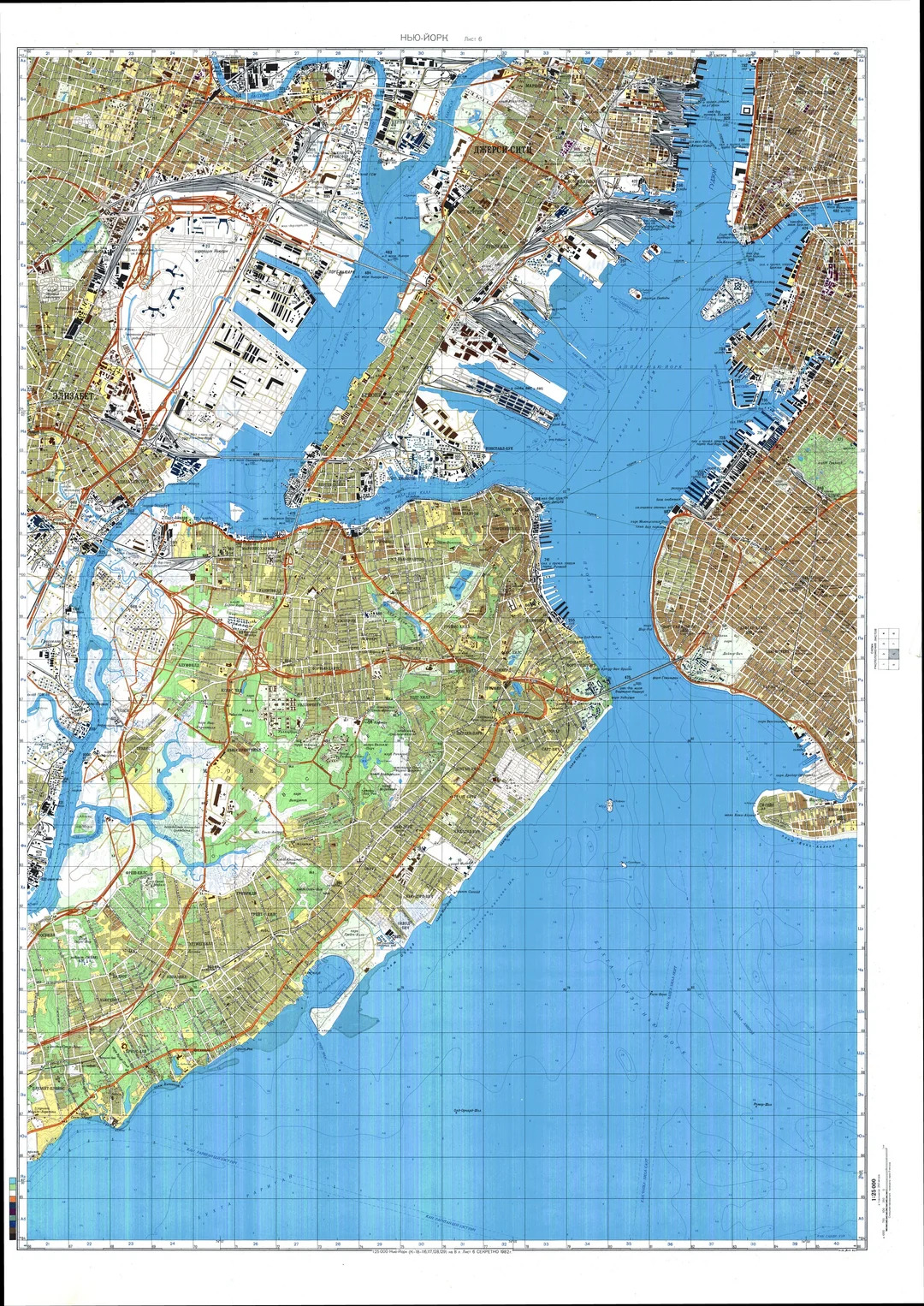

Nowhere was the USSR’s obsession with mapping more apparent than in its treatment of foreign territory—especially the West.

From the perspective of U.S. military intelligence, it came as a shock in the 1990s to learn just how thoroughly the Soviets had mapped American cities, down to individual factories and freight yards.

Cities like Chicago, Boston, and San Francisco were rendered in mind-boggling detail.

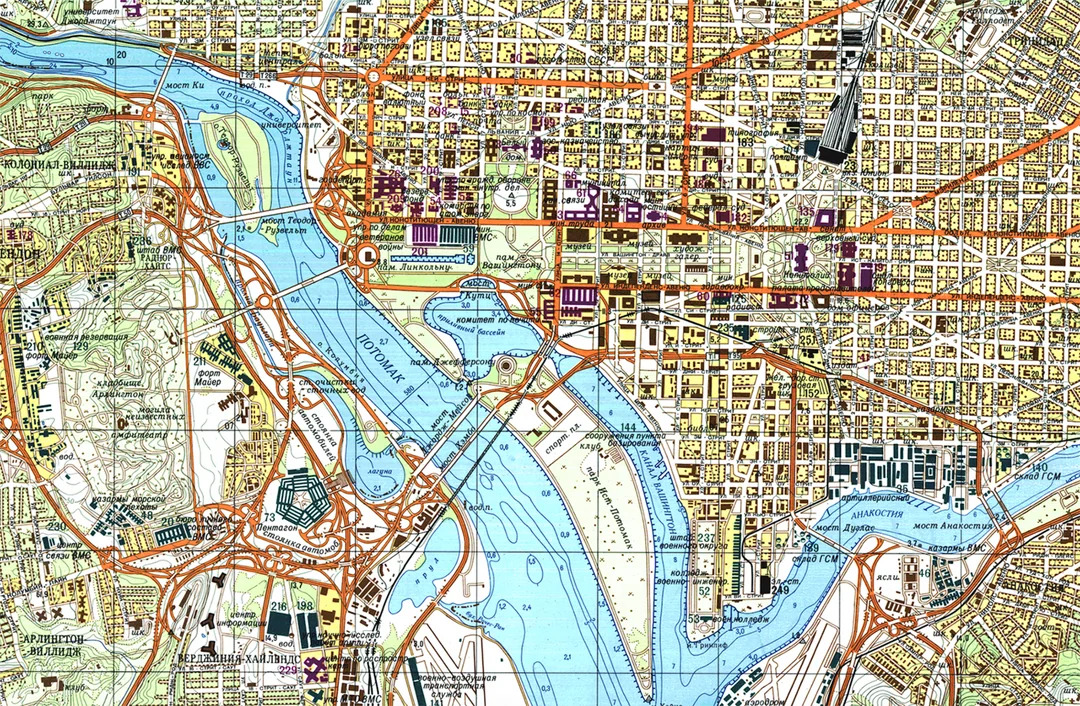

The Soviet 1:10,000 map of Washington, D.C., for example, contains thousands of individual structures. Each is marked not just by shape, but by function. A school is labeled as a school. A government agency is identified by name and, where known, purpose. Sewers, electrical substations, and underground rail tunnels are all included.

One widely cited example is the Soviet map of Manhattan.

It includes detailed building footprints, the depths of the Hudson and East Rivers, port facilities, tunnel elevations, and the width of every major street.

For planners, this information would be essential not just for potential invasion scenarios, but for the deployment of paratroopers, the placement of airstrikes, or the disruption of logistics.

The most impressive aspect was that the Soviets often produced better maps of Western cities than the cities themselves possessed.

In London, for instance, the Soviet maps identified military barracks and classified facilities omitted from any UK Ordnance Survey map. In the U.S., where the National Mapping Program often left rural regions less surveyed, Soviet maps filled in the blanks with uncanny accuracy.

How did the USSR obtain all this? Beyond satellites and spies, they used creative means: studying foreign newspapers and real estate ads to map neighborhoods; analyzing TV broadcasts for city layouts; and sending operatives to tourist sites with concealed instruments.

The result? A map of the world that was more complete—and more secret—than anything else that existed.

Accuracy and Anomalies

The quality of Soviet maps was not merely good for their time—they were, in many cases, ahead of their time.

Western experts who encountered these maps in the 1990s and 2000s often described them as “shockingly detailed” or “eerily complete.” Some wondered how such precision could be achieved without access to Western GPS technology or open-source satellite imagery.

The answer lies in a combination of rigor, scale, and ingenuity.

Elements of Accuracy

Soviet maps were known for capturing the following details with remarkable consistency:

- Building Dimensions and Functions: Large industrial buildings, government facilities, schools, and hospitals were not only drawn to scale but labeled with their use. In some urban maps, even warehouses and garages were tagged with specific operational notes.

- Road Grading: Roads were categorized by width, surface material, and load capacity. This was critical for military logistics, determining whether heavy armor could traverse a given route or whether air transport was required.

- Bridges and Tunnels: Not just their location, but structural details—height, construction material, and maximum safe tonnage—were included. Many U.S. infrastructure analysts later confirmed that Soviet data on American bridges was surprisingly up to date.

- Coastlines and Ports: Harbor depths, tidal patterns, and navigational hazards were recorded. This data, vital for amphibious operations, often rivaled or exceeded that of NATO maritime charts.

- Contours and Elevation: Contour lines at 5- or 10-meter intervals gave commanders a three-dimensional view of the terrain. In mountainous areas, Soviet maps often included avalanche zones, river fords, and passability by season.

- Subterranean Features: In some maps, especially of major cities, underground metro lines, sewage systems, and service tunnels were annotated—suggesting extensive reconnaissance or collaboration from local informants.

How They Achieved It

- Triangulation Networks: Soviet surveyors built a grid of physical reference points across continents, allowing for precise measurements from multiple angles. These could then be mathematically extended into foreign regions using known data.

- Spy Photography: High-altitude aircraft and satellite systems (like the Zenit series) captured imagery for cartographers to analyze. Soviet imaging technology may have lagged behind U.S. programs like CORONA in resolution but compensated with frequency and volume.

- Open-Source Scrutiny: Everything from tourist guidebooks to real estate brochures, architectural digests, and local newspapers were combed through for clues. A casual mention of a new hospital wing or a road resurfacing project could result in a map update.

- Human Intelligence: KGB and GRU officers collected terrain intelligence during diplomatic assignments, cultural exchanges, or even student visits. In some cases, Soviet allies in socialist countries (like East Germany or Cuba) supplied topographic surveys directly.

When They Got It Wrong

Despite their excellence, Soviet maps weren’t perfect.

Some maps showed obsolete factory layouts or misnamed neighborhoods. Others overemphasized military significance—turning amusement parks into presumed radar stations or industrial centers.

These errors fell into three main categories:

- Misinterpretation: A foreign landmark might be misunderstood due to cultural context—e.g., mistaking a university for a military academy.

- Deliberate Deception: Some maps were created with intentional flaws to mislead potential captors. These versions were likely reserved for lower-security circulation or decoy use.

- Data Lag: In regions with limited spy access (like parts of Africa), the USSR relied heavily on older British colonial maps, resulting in outdated information by the 1980s.

Nevertheless, the ratio of accuracy to error was extraordinarily high.

The depth of Soviet geographic intelligence startled Western analysts and raised uncomfortable questions: If they knew this much about us, what else had we underestimated?

Secrecy and Discovery

The Iron Curtain didn’t just keep people out—it kept information in.

For nearly half a century, Soviet cartography operated in near-total darkness. Civilian Soviet maps were intentionally falsified. Even Soviet scientists had to work with distorted or scaled-down maps, as the high-resolution ones were considered military assets.

The secrecy was so pervasive that entire Soviet cities remained “off the map.” Known as closed cities, these places were home to nuclear labs, missile silos, and elite military academies. They were often marked only by a postal code or referred to by a number (e.g., Arzamas-16).

To this day, some of these cities remain restricted.

The curtain lifted after the USSR’s collapse in 1991. As the new Russian Federation struggled to stabilize, the former Soviet republics became treasure troves of forgotten files. In places like Riga and Vilnius, former military warehouses were sold off, and their contents—including secret maps—were either dumped or leaked onto the black market.

Western scholars and map collectors began acquiring these documents, often paying modest sums for materials that would’ve once triggered an international incident. In some cases, entire sets of regional maps were smuggled out and scanned for posterity.

The magnitude of the discovery sparked awe.

British geographer John Davies, who became a leading authority on the topic, described finding Soviet maps of tiny Welsh villages—places that had never even warranted mention on national maps. Their presence in Soviet archives revealed the extent to which the USSR believed that no detail was too small.

Soon, universities and intelligence agencies in the U.S., Canada, and Europe began digitizing these maps and analyzing them.

Not only were they accurate—they provided a snapshot of Cold War thinking. What the Soviets chose to map, and how they depicted it, revealed their military concerns, ideological priorities, and global ambitions.

Legacy and Modern Implications

Today, Soviet maps are no longer state secrets. Many have been digitized, archived, and studied by universities, government agencies, and historians.

They offer a rare glimpse into the mindset of Cold War planners—a world where detailed knowledge of foreign infrastructure was essential for survival, and where cartography was a tool of both domination and defense.

In some parts of the world, these maps are still in use.

In countries with limited mapping resources—particularly in parts of Africa, Asia, and South America—Soviet maps are sometimes the most detailed and accurate available. Aid workers, engineers, and geographers continue to consult them for infrastructure planning and logistical operations.

Moreover, the Soviet cartographic legacy has influenced modern practices in geographic information systems (GIS), satellite mapping, and military intelligence.

The idea that mapping can be both a scientific and strategic pursuit lives on in today’s world of digital surveillance, drone reconnaissance, and data-driven planning.

There’s also a philosophical legacy.

The Soviet maps remind us that knowledge—especially geographic knowledge—is power. In an age of open data and global positioning systems, the idea of a secret, state-controlled map archive seems archaic. Yet the Soviets proved that with enough determination, bureaucracy, and paranoia, you could chart the world without the world knowing.

Geographical Knowledge Behind the Iron Curtain: Final Thoughts

The Soviet Union's secret mapping project remains one of the most impressive—and chilling—feats of the Cold War.

At a time when data was scarce, the USSR managed to create an atlas of the world so precise that it still holds value today. These weren’t just maps; they were strategic blueprints, visualized ideologies, and instruments of geopolitical control.

In retrospect, they also reveal the vast energies poured into the Cold War—where even geography became a weapon, and understanding your enemy meant knowing not just where they were, but how they lived, moved, and planned.

As digital tools replace paper charts, and satellites map every street in real-time, the Soviet cartographers stand as a testament to what can be achieved through sheer will, secrecy, and scientific discipline.

Their maps tell us not just where things were, but how one superpower saw the world—and what it was prepared to do to control it.