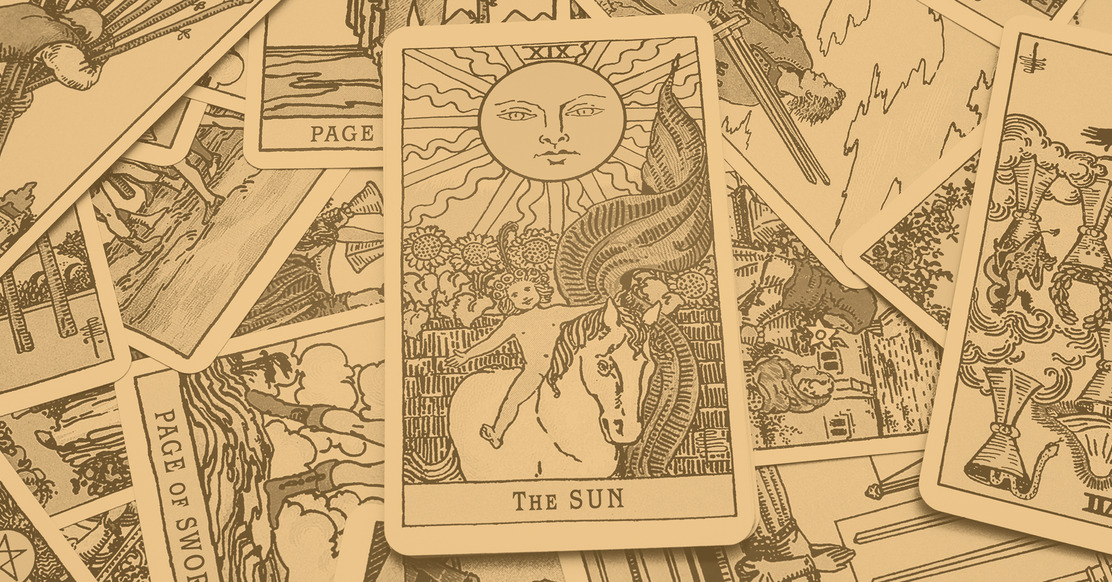

The History of Tarot Cards: From Fortune-Telling to Modern Art

Tarot cards have long occupied a space between the mystical and the mundane, the artistic and the esoteric.

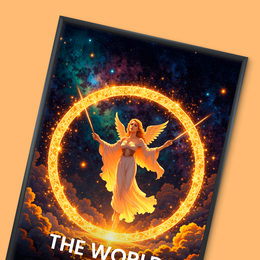

For some, they’re mysterious tools used by fortune tellers under candlelight; for others, they’re simply beautiful pieces of art, collected and admired for their aesthetic value, such as custom Tarot Card poster. But the story of tarot cards is far more layered than either of these perspectives suggests.

Rooted in centuries-old card games and transformed through generations of cultural reinvention, tarot cards have evolved into complex symbols of human consciousness, spiritual exploration, and visual storytelling.

The allure of tarot is not just in its visuals or its historical mystique. At its heart, tarot is about stories—the ones we tell ourselves, the ones we interpret from the cards, and the ones we create through engaging with the symbols.

Whether approached as a tool for fortune-telling, a mirror for self-reflection, or a collectible piece of artwork, tarot invites people to explore the human experience in all its mystery and meaning.

Origins of Tarot: A Game Before a Gateway

Long before tarot was cloaked in mysticism, spiritual symbolism, and esoteric meanings, it was a card game—a pastime enjoyed by European aristocracy during the Italian Renaissance.

Contrary to popular belief, the tarot deck was not originally intended for fortune-telling. Instead, it emerged as a trick-taking game known as Tarocchi in Italy, Tarot in France, and Tarock in parts of central Europe.

Its earliest surviving examples offer more insight into the evolution of European art and society than the mysteries of the occult.

The first known tarot decks appeared in the 15th century, commissioned by noble families such as the Visconti and Sforza dynasties of Milan. These early decks, now collectively referred to as the Visconti-Sforza tarot, were meticulously hand-painted and gilded with gold, reflecting the artistic grandeur of the time.

The cards featured not just playing suits, but also elaborate allegorical figures, like The Emperor, The Lovers, and The Wheel of Fortune. However, these figures were not yet imbued with mystical meanings—they were artistic embellishments, more reflective of cultural values and courtly life than of divinatory wisdom.

The structure of these early decks already resembles what we now recognize as the modern tarot.

A complete deck included four suits (typically swords, cups, coins, and batons), similar to modern playing cards, each with ten pip cards and four court cards (page, knight, queen, king).

What distinguished tarot from other decks was the addition of 21 trump cards—later known as the Major Arcana—and a special unnumbered card, Il Matto, or The Fool. These trump cards were used to outplay other cards in a game format and were not originally symbolic of spiritual lessons or mystical pathways.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, tarot spread across Europe, particularly into France and Switzerland, where the game evolved and became increasingly popular.

The decks became more standardized, especially with the creation of the Tarot of Marseille, a version that would later play a pivotal role in the occult interpretation of tarot. Even so, for hundreds of years, tarot remained a secular form of entertainment.

It wasn’t used for divination in any widespread or organized fashion, and the belief that the cards held ancient, mystical wisdom was not yet part of the narrative.

It's important to understand that during this period, Europe was undergoing profound cultural transformation. The Renaissance sparked renewed interest in classical knowledge, artistic expression, and the natural sciences.

The invention of the printing press also allowed decks to be more widely distributed, making tarot accessible to broader audiences. But it would still be several centuries before tarot would take on the mystical identity it holds today.

In hindsight, it’s fascinating that something created for leisure—a glorified version of a parlor game—would eventually be embraced as a profound spiritual and psychological tool.

The early tarot decks were not mystical texts, but they laid the foundation for future reinterpretations. The images and symbols used in these original decks, although created with artistic and cultural intent rather than spiritual depth, proved fertile ground for later generations to read between the lines.

Tarot’s journey from game to gateway didn’t happen overnight. It was a slow transformation, shaped by shifting ideologies, philosophical inquiries, and the human desire to find meaning in symbols.

The Occult Revival: Tarot as a Tool for Divination

By the 18th century, tarot began to experience a dramatic metamorphosis.

What had once been an ornate card game for the European elite was now being viewed through a mystical lens. This pivotal period saw the tarot absorbed into the esoteric traditions of Western occultism, radically redefining the purpose and perception of the cards.

No longer just a game, tarot became a gateway to hidden knowledge, spiritual insight, and cosmic understanding.

The Start of the Mystical Tarot

The transformation can largely be traced to a single man: Antoine Court de Gébelin, a French clergyman and Freemason with a deep interest in the symbolic language of mythology and ancient civilizations.

In 1781, de Gébelin published a multi-volume work titled Le Monde Primitif, in which he claimed that the tarot contained ancient wisdom originating in Egypt.

According to his speculative theory, tarot was a book of esoteric knowledge disguised in the form of a card game, created by Egyptian priests and preserved through the ages.

De Gébelin’s assertions were based more on imagination and symbolic interpretation than on historical evidence. At the time, very little was known about ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs or culture, making it easy for romantic ideas about “lost wisdom” to take root.

Despite the lack of factual support, de Gébelin’s ideas had an enormous influence. His framing of tarot as a mystical artifact rather than a leisure item sparked new interest among occultists and spiritual seekers.

The Elevation the Tarot

One of the earliest figures to build on this reinterpretation was Jean-Baptiste Alliette, who wrote under the pseudonym Etteilla (his surname spelled backward). Etteilla was a French occultist who, inspired by de Gébelin’s theories, developed the first tarot deck explicitly designed for divination.

He published guides on how to use the cards to read the future and even created his own esoteric system of meanings, complete with associations to astrology, the four classical elements, and the supposed “Book of Thoth,” an ancient mythical text said to hold the secrets of the universe.

Etteilla’s work laid the groundwork for tarot as a tool for fortune-telling.

He gave each card specific meanings based on upright and reversed positions, creating a structure that readers could follow.

He also began to associate the tarot with the Kabbalah, a form of Jewish mysticism that explores the hidden dimensions of reality through a system of sacred numbers, letters, and paths.

This association deepened the spiritual significance of the cards and set the stage for the more formalized systems that would arise in the 19th century.

The Rise of the Metaphysical

In the decades that followed, secretive groups like the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn would adopt and expand tarot’s mystical associations.

They saw the tarot as a symbolic representation of universal laws, a key to understanding the mysteries of the soul and the structure of the cosmos. Each card was linked to specific astrological signs, elements, sephiroth on the Tree of Life, and even alchemical principles.

Within this framework, the Major Arcana—cards like The Magician, The High Priestess, and Death—were elevated to archetypal figures in a grand metaphysical journey.

They represented stages of spiritual development and transformation. The Minor Arcana were no longer just suits for gaming but were interpreted as expressions of elemental energies and real-life situations.

The occult revival gave tarot its modern metaphysical backbone. From this point forward, tarot was no longer viewed primarily as a game, but as a symbolic system used for personal insight, spiritual development, and prophecy.

This transition was so successful that today, many people believe tarot was always intended for fortune-telling—even though that interpretation is a relatively recent overlay on a much older tradition.

This period of esoteric reinvention not only elevated tarot’s cultural and spiritual status but also paved the way for the creation of standardized decks and reading methods.

As the 20th century approached, tarot was poised for another transformation—this time, one that would blend esotericism with modern psychology and visual innovation.

The Rider-Waite-Smith Revolution

The modern image of tarot as a visually rich, psychologically resonant tool for divination owes much to a single deck: the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot.

Published in 1909, this deck marked a turning point in tarot’s history, not only in design but in accessibility and function.

Its creators—Arthur Edward Waite, a British occultist and member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and Pamela Colman Smith, a Jamaican-British artist and illustrator—combined esoteric knowledge with artistic innovation to create a deck that would become the global standard for tarot reading.

A New Vision for Tarot Imagery

Prior to the Rider-Waite-Smith (RWS) deck, most tarot designs—such as the Tarot of Marseille—featured detailed illustrations only in the Major Arcana and court cards.

The numbered Minor Arcana cards were typically simple, often showing the suit’s symbol repeated across the card with little or no illustrative content. This design made the Minor Arcana more difficult to interpret intuitively, especially for novices.

Smith’s contribution changed everything. Under Waite’s guidance, she illustrated all 78 cards in the deck, including narrative scenes for every Minor Arcana card. This innovation made the entire deck accessible for storytelling, symbolism, and interpretation.

Suddenly, a card like the Ten of Swords didn’t just feature ten swords—it depicted a figure lying prone with swords in his back, under a dramatic sky. These scenes gave readers emotional cues and archetypal meaning that extended beyond the abstract or numerological interpretations used in earlier decks.

Her style was heavily influenced by stage design, mysticism, and the Symbolist art movement, resulting in imagery that felt both theatrical and deeply symbolic.

While the art might seem simple or even naïve at first glance, the cards are rich in layered meaning, color theory, and psychological depth.

Waite’s Influence and Esoteric Structure

Arthur Edward Waite, for his part, brought a scholarly and mystical perspective to the deck’s structure.

Unlike Etteilla, whose meanings were often imaginative and speculative, Waite aimed to distill the teachings of the Golden Dawn into a system that would resonate with both spiritual seekers and average people.

His guidebook, The Pictorial Key to the Tarot, laid out upright and reversed meanings for each card, grounded in Western esotericism, Christian mysticism, and Kabbalistic philosophy.

One key change Waite made was switching the order of two Major Arcana cards—Strength and Justice—so that Strength became card VIII and Justice XI.

This adjustment aligned the deck more closely with astrological correspondences used by the Golden Dawn, even though it broke with tradition. Over time, Waite’s system became dominant in English-speaking tarot traditions.

Cultural Legacy and Enduring Popularity

The RWS deck’s cultural impact cannot be overstated. It was the first tarot deck to achieve widespread commercial success, thanks in part to its publication by the Rider Company in London.

But it was also the first deck that spoke directly to readers without requiring them to memorize arcane symbols or study dense occult texts.

With its expressive imagery and clear symbolism, it invited users to rely on intuition as much as knowledge—a concept that remains at the heart of modern tarot practice.

Despite its popularity, it’s only in recent decades that Pamela Colman Smith has received widespread recognition for her role. For many years, the deck was credited solely to Waite and the publisher, Rider.

Today, tarot scholars and practitioners make a point of honoring Smith's legacy by including her name in the title: Rider-Waite-Smith.

The deck's influence continues to ripple outward.

Countless modern tarot decks draw inspiration from the RWS system in structure, symbolism, and style. Even alternative decks that break from tradition often do so in deliberate conversation with the Rider-Waite-Smith model.

Whether you're a seasoned tarot reader or a curious beginner, chances are your first deck—or your favorite one—traces its lineage back to the revolutionary work of Waite and Smith.

Tarot in the 20th Century: Pop Culture and Psychology

The 20th century ushered tarot into mainstream consciousness, liberating it from the tightly held circles of secret societies and positioning it within broader spiritual, artistic, and psychological discourse.

It was a century of massive transformation—not just for society, but for the tarot itself. The cards became tools for healing, storytelling, rebellion, and self-reflection.

In the process, they found a home not only in mystical practices but also in psychotherapy offices, pop culture, and personal spirituality.

The Rise of the New Age Movement

During the 1960s and 1970s, a global wave of spiritual curiosity and countercultural exploration gave rise to what is now known as the New Age movement.

This era embraced alternative spirituality, metaphysics, and non-Western philosophies, including astrology, yoga, energy healing, and tarot. People were searching for meaning outside institutional religion, and tarot offered an accessible, symbolic system that invited personal interpretation.

It was during this time that tarot began to proliferate as a tool for personal growth rather than strict fortune-telling. While many still approached the cards with questions about love, money, and destiny, the tone shifted.

Tarot readings became more therapeutic—centering on self-awareness, decision-making, and spiritual evolution. This reframing laid the groundwork for tarot’s acceptance in more psychological and even academic circles.

Jungian Psychology and Archetypes

Perhaps the most important bridge between tarot and psychology was constructed by Carl Jung, the Swiss psychiatrist whose theories continue to influence spiritual thought today.

Jung didn’t write specifically about tarot, but his work on archetypes, the collective unconscious, and symbolic systems offered a profound psychological lens through which tarot could be understood.

To Jung, archetypes are universal patterns of behavior and thought shared by all humans—such as the Hero, the Shadow, the Mother, and the Fool. These figures are mirrored in the Major Arcana of tarot, making the deck an almost perfect tool for exploring the psyche.

The Fool’s journey through the 22 Major Arcana cards can be read as a metaphor for an individual’s journey through life, confronting various aspects of the self along the way.

Tarot readers inspired by Jung began using the cards in ways that mirrored active imagination—a Jungian technique of dialoguing with inner parts of the psyche. A reading became less about “what will happen to me?” and more about “what story am I living, and how can I change it?”

Tarot in Literature, Music, and Film

Parallel to its psychological resurgence, tarot began to appear more frequently in popular culture—sometimes as a dramatic narrative device, other times as a symbol of fate, chaos, or hidden knowledge.

Tarot cards show up in classic films like Live and Let Die (1973), where the mysterious Solitaire uses tarot to predict James Bond’s fate, and The Holy Mountain (1973), in which a mystical alchemist uses tarot imagery to convey cosmic truths.

Novels such as Italo Calvino’s The Castle of Crossed Destinies used tarot to structure entire storylines, and musicians like Tori Amos, David Bowie, and Stevie Nicks incorporated tarot symbolism into their lyrics, fashion, and stage presence.

These appearances weren’t always accurate portrayals, but they cemented tarot’s role as a symbol of mystery, transformation, and rebellion. As more people encountered the cards through movies and books, curiosity often led them to explore the real thing.

As tarot moved through the 20th century, it evolved from a fringe occult artifact into a dynamic, multipurpose tool for personal insight and cultural commentary. No longer just a means of telling fortunes, the tarot became a mirror of the times—adapting to new philosophies, art styles, and social movements while still retaining its core symbolic power.

Tarot Today: From Divination to Design

In the 21st century, tarot has undergone yet another radical transformation—one that merges spirituality with creativity, personal expression with artistic exploration.

While tarot is still widely used as a tool for divination and introspection, its role has expanded far beyond the borders of mysticism.

Today, tarot is equally at home in art galleries, Kickstarter campaigns, wellness apps, and Instagram feeds. This era of tarot is defined not by a single tradition, but by plurality, personalization, and a renewed emphasis on design.

The Indie Deck Boom

One of the most notable trends in contemporary tarot is the independent publishing explosion. Today, artists and spiritual practitioners no longer need to go through major publishing houses to create and distribute their own decks.

Instead, they can crowdfund their ideas, reach global audiences directly, and retain full creative control over their vision.

This shift has produced a breathtaking variety of decks, each reflecting the unique voice and worldview of its creator. Some are deeply rooted in tradition, carefully honoring the Rider-Waite-Smith format or Marseille style.

Others are wildly experimental, incorporating photography, digital collage, pop culture references, or abstract art. There are decks themed around everything from Japanese folklore to Afrofuturism to queer identity to herbal medicine.

Some feature minimalist aesthetics; others are lush, baroque, or psychedelic.

No longer confined to esoteric symbolism or Eurocentric archetypes, modern tarot decks have become vehicles for inclusion and representation. Artists are consciously creating decks that feature diverse bodies, ethnicities, genders, and life experiences.

This movement has made tarot more accessible and empowering for a much broader audience—one that often finds mainstream decks lacking in cultural relevance.

Tarot as a Tool for Healing and Self-Care

Contemporary tarot is also deeply connected to the self-care and wellness movements. Readers today often position tarot less as a fortune-telling device and more as a mirror for the subconscious—a way to engage with emotions, fears, goals, and personal narratives.

Rather than asking, “What will happen to me?” many people now approach the cards with questions like, “What should I be focusing on?” or “How can I better understand this situation?”

This shift has blurred the line between tarot reader and therapist. While tarot is not a substitute for professional mental health care, many practitioners use it in therapeutic or coaching settings to foster reflection and emotional clarity.

Guided tarot journaling, meditation prompts tied to specific cards, and therapeutic spreads are increasingly common. The cards become catalysts for dialogue—whether with a reader, a therapist, or oneself.

Apps like Labyrinthos, Golden Thread Tarot, and Luminous Spirit have brought these practices into the digital age, offering daily card pulls, digital journals, and learning tools for users seeking clarity or growth.

The presence of tarot in the wellness space reflects a broader cultural hunger for meaning and mindfulness in an often chaotic world.

From Tarocchi to Tarot: A Long Journey

Tarot cards have never remained static.

From their playful origins as Renaissance-era entertainment to their role in the mystical philosophies of the 18th and 19th centuries, from tools of spiritual inquiry and psychological insight to icons of modern design and art, tarot has continually adapted to meet the needs and aesthetics of each generation.

Their endurance across centuries speaks not just to the beauty of the cards themselves, but to their incredible capacity for reinvention.

At their core, tarot cards are about meaning—how we seek it, how we create it, and how we express it.

What makes tarot so compelling is its dual nature. It’s structured yet flexible. Ancient yet contemporary. Deeply personal, yet universally archetypal. The same card can mean something entirely different depending on the deck, the question asked, or the person drawing it.

Tarot is a conversation, not a command. It doesn’t dictate the future but illuminates the present, suggesting pathways, emotions, and possibilities.

This fluidity is what allows tarot to thrive in the modern world. In an age when spirituality is often self-directed and eclectic, tarot offers a non-dogmatic system for reflection and growth.

In a culture increasingly visual and design-driven, tarot provides an artistic format that encourages storytelling and experimentation. It exists at the intersection of intuition and intellect, mysticism and materialism, ritual and aesthetics.

In the end, the history of tarot is not just the history of a deck of cards. It is the history of how we, as individuals and societies, search for understanding, connection, and beauty in a world that rarely offers clear answers.

Tarot invites us to look inward and outward at once—offering not certainty, but insight; not prophecy, but perspective. And in that offering, it becomes timeless.