Ptolemy’s Geography: The Ancient Mapmaker Who Shaped the World

Long before satellites hovered above Earth and digital maps fit neatly into our pockets, the ancient world relied on the work of a visionary who sought to chart the world using logic, mathematics, and observation.

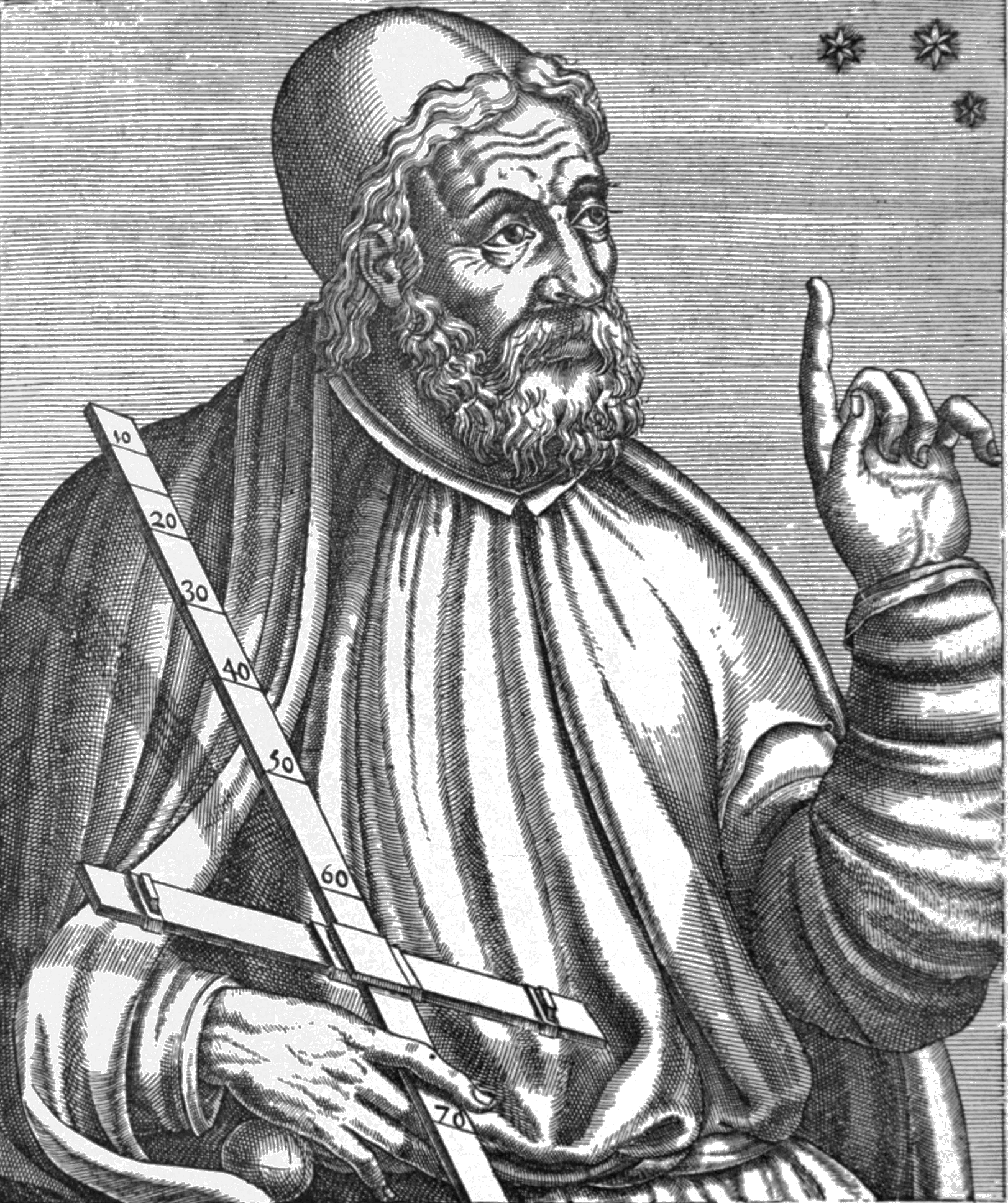

Claudius Ptolemy, a Greco-Roman scholar working in 2nd century Alexandria, produced one of the most influential geographical works in human history. More than a mere compilation of places and names, this old map print was a systematic treatise that introduced a scientific approach to mapping the Earth.

Ptolemy's efforts did not simply mirror his contemporary understanding of the world—they included a revolutionary idea that provided a framework that would influence geographic thinking and cartographic practices for over a millennium— the notion that the Earth's surface could be accurately represented on paper through a mathematical coordinate system.

Despite its inaccuracies, Geographia laid the groundwork for future advancements, influencing generations until modern geography surpassed his model. Yet the impact remains undeniable—Ptolemy endures not only as a geographer but as one of the most influential minds in the history of science and discovery.

Who Was Ptolemy?

Claudius Ptolemy remains one of the most influential figures of antiquity, a polymath whose work spanned the disciplines of astronomy, mathematics, astrology, music theory, optics, and of course, geography.

Despite his vast intellectual legacy, surprisingly little is known about Ptolemy’s personal life.

Scholars believe he lived and worked in Alexandria, Egypt—then a prominent center of learning within the Roman Empire—during the 2nd century CE. Most commonly, his active period is dated from around 127 to 180 CE, though exact dates remain uncertain.

Alexandria, where Ptolemy likely lived and worked, had long been a hub of knowledge and inquiry. Home to the Great Library and the Museum (a research institution, not a gallery), Alexandria attracted thinkers from across the Mediterranean world.

Ptolemy’s access to such a wealth of texts and scholars would have greatly enriched his work. His ability to synthesize centuries of prior knowledge into a structured system is one of his defining achievements.

Major Contributions

Ptolemy’s most enduring contributions lie in three major works: The Almagest, Tetrabiblos, and Geographia.

The Almagest is arguably his most famous, outlining a geocentric model of the universe that placed Earth at its center with the planets, sun, and stars orbiting around it.

Though later disproven by Copernicus and Galileo, this model dominated Western and Islamic astronomy for over 1,400 years and demonstrated Ptolemy’s extraordinary skill in creating a mathematically consistent system that matched observable data—at least to the naked eye.

In Tetrabiblos, Ptolemy addressed astrology, which at the time was regarded as a legitimate field of study alongside astronomy. He sought to give it a rational foundation, correlating celestial phenomena with human affairs.

Though astrology has since been relegated to the realm of pseudoscience, Tetrabiblos influenced astrological thought for centuries and cemented Ptolemy’s reputation as an authority in celestial studies.

It is, however, Geographia that concerns us most in this context—a text that represents his effort to map the known world using mathematical principles. Unlike previous geographers, who focused on narrative descriptions or artistic renderings, Ptolemy approached geography with the rigor of a scientist.

He aimed not only to describe lands and regions but also to mathematically plot them based on a grid of latitude and longitude. This approach was pioneering and stood in stark contrast to the often symbolic or mythological maps of his predecessors.

Ptolemy’s role was not that of a discoverer or explorer. He did not travel to chart distant lands or gather firsthand observations. Instead, he was a synthesizer of knowledge—a compiler of data from earlier sources such as Marinus of Tyre, Roman itineraries, and reports from merchants and travelers.

He refined, corrected, and systematized this information into a cohesive framework that others could use to construct maps. This analytical approach made his work unusually enduring and adaptable.

Ptolemy was a figure who bridged cultures, disciplines, and centuries. He stood at the crossroads of Greek intellectual tradition and Roman administrative practicality, producing works that were not only relevant to his own time but would come to shape the worldviews of generations to come.

The Creation of Geographia

The third and perhaps most ambitious of Ptolemy’s great works was Geographia, a monumental treatise that sought to define the physical world through scientific and mathematical principles.

Unlike previous geographical texts that focused largely on descriptive storytelling or mythological frameworks, Geographia aimed to provide a method for rendering the known world into a mappable, reproducible form.

At its heart was a vision of geography not just as knowledge of places, but as a precise discipline based on measurable data.

Geographia is composed of eight books.

The first book lays out the theoretical foundations of geography—what it is, how it should be practiced, and the principles behind mapmaking. Here, Ptolemy discusses the challenge of projecting the spherical Earth onto a flat surface, proposing several mathematical projections to solve this problem.

This section is where Ptolemy most clearly establishes his belief that geography could—and should—be grounded in mathematical precision.

Books two through seven contain exhaustive gazetteers, listing coordinates (in degrees of latitude and longitude) for over 8,000 locations spanning Europe, Asia, and Africa. The eighth and final book describes how to construct maps from this data, organized into regional sections.

Geographia: Citing the Sources

Creating Geographia required Ptolemy to synthesize information from a vast array of sources. He relied heavily on the earlier work of Marinus of Tyre, a geographer who lived in the late 1st to early 2nd century CE.

Marinus had already developed a rudimentary system of latitude and longitude and had compiled extensive geographic data, but his methods lacked consistency. Ptolemy took these raw materials and refined them, correcting perceived inaccuracies and reworking Marinus’s system into something far more robust and coherent.

Beyond Marinus, Ptolemy drew from Roman itineraries, administrative records, travel narratives, astronomical data, and maritime logbooks. While he rarely traveled himself, he showed considerable skill in evaluating and integrating second-hand reports.

He often adjusted distances based on celestial observations—calculating how the length of daylight or the elevation of stars changed with latitude, for instance.

Although much of his data was imprecise or outdated, the method by which he treated and organized it marked a turning point in the history of geography.

A Map to Innovation

One of Ptolemy’s key innovations was his emphasis on coordinates.

He assigned each location a pair of values—latitude measured from the equator and longitude measured from a prime meridian that he located at the “Fortunate Isles,” believed to be the Canary Islands.

This allowed anyone with the text to reconstruct maps with reasonable consistency, regardless of artistic skill or firsthand knowledge of the terrain.

In doing so, Ptolemy established a universal system for spatial orientation that resembled the Cartesian coordinate system centuries before Descartes formalized it.

Mapmaking Mishaps

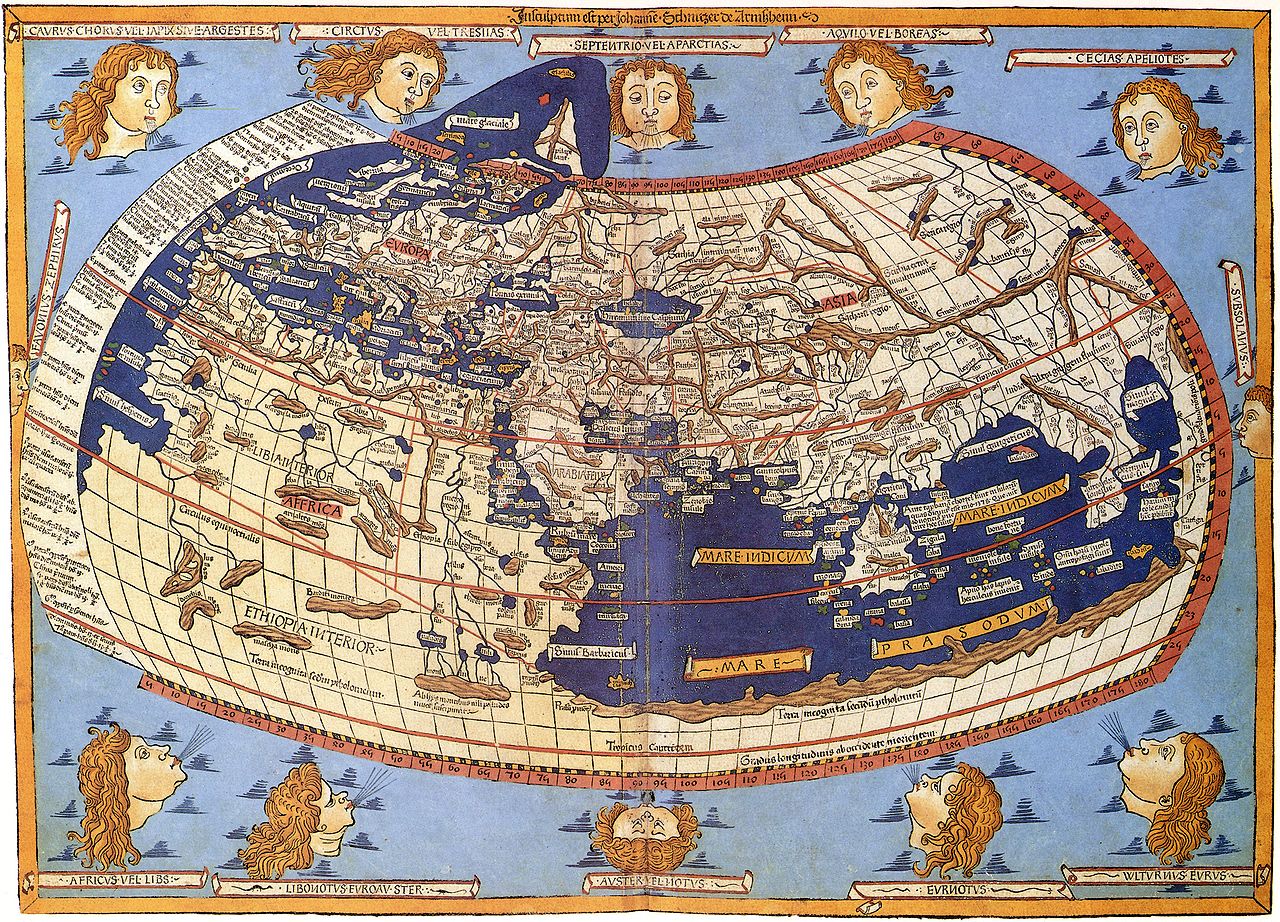

Despite these groundbreaking strides, Ptolemy’s work was not without errors. His map projected the known world as stretching 180 degrees in longitude and 80 degrees in latitude, omitting vast swaths of the globe, including the entirety of the Americas, Australia, and much of sub-Saharan Africa.

He also drastically underestimated the Earth’s circumference, which had significant consequences centuries later during the Age of Exploration.

Nevertheless, the very act of attempting a mathematically precise rendering of the world set Geographia apart from any geographic work that came before it.

Ptolemy’s maps were originally conceptual—intended to be drawn by readers using the data and methods he supplied. The earliest known surviving Ptolemaic maps were likely created by Byzantine scholars centuries after his death.

These visualizations, though imperfect, served as tangible representations of Ptolemy’s geographic worldview and were reproduced extensively after the text was translated into Latin in the 15th century.

Ultimately, Geographia was an extraordinary intellectual achievement: a marriage of Greek theoretical reasoning and Roman empirical data collection.

In transforming geography from a subjective narrative into an objective science, Ptolemy created not just a book of maps but a framework for understanding the Earth through reason, geometry, and observation.

It was this framework—more than any individual map—that would go on to shape geographic thinking for more than a thousand years.

The World According to Ptolemy

Ptolemy’s Geographia was a bold attempt to capture the entire known world of his time in a single, coherent system—a feat that no one before him had accomplished with such mathematical rigor. But what exactly did the world look like through Ptolemy’s eyes?

His maps and data provide a fascinating snapshot of second-century geographic knowledge, complete with a mix of astonishing insights, classical misconceptions, and substantial gaps that reflect both the limits and ambitions of ancient science.

At the heart of Ptolemy’s worldview was the Roman Empire, particularly the Mediterranean basin. This region, familiar through trade routes and administrative oversight, was mapped with relative precision.

Cities like Rome, Alexandria, Athens, and Carthage were plotted with coordinates that placed them in plausible relative positions. Ptolemy referred to this central area as the “Oikoumene”—the inhabited world—an idea inherited from earlier Greek geography but expanded upon significantly in both detail and scope.

To the north, Ptolemy charted parts of Europe, including the British Isles, Germany, Gaul (modern France), and Scandinavia. While he attempted to map these northern regions using reports from Roman expeditions and trading routes, many of the shapes and positions were distorted.

In Africa, Ptolemy focused on the northern and eastern regions—Libya (North Africa), Egypt, and the Red Sea coast—which were better known to the Roman world. He depicted the Nile River flowing from a chain of lakes in central Africa, an idea that endured in Western maps well into the 17th century.

However, his portrayal of sub-Saharan Africa was vague and speculative. He also believed, incorrectly, that the Indian Ocean was enclosed by land on the south and east, essentially forming a large, inland sea.

This assumption would later influence European explorers who sought routes around Africa to reach Asia, only to be surprised when the ocean opened into wider global waters.

Asia, as described by Ptolemy, stretched as far east as the land of “Sinae” (China) and “Serica” (likely referring to regions producing silk). India received extensive treatment, thanks to trade and maritime routes connecting the Roman Empire with the Indian subcontinent.

However, the size and placement of Asia were significantly exaggerated, especially in longitude. Ptolemy’s miscalculation of Earth’s circumference led him to compress longitudes, making Asia appear much wider than it truly is.

This mistake would have lasting implications. Centuries later, Christopher Columbus, using maps derived from Ptolemaic geography, believed that sailing west from Europe would bring him directly to the coast of Asia—unaware of the vast American continents in between.

Perhaps the most glaring omissions from Ptolemy’s world are the Americas, Australia, and much of sub-Saharan Africa. These areas lay beyond the horizon of known geography in his time and were absent from all ancient records.

Yet rather than leaving empty spaces on his maps, Ptolemy and his successors often filled in the blanks with imaginative or theoretical landmasses. For example, the southern hemisphere included a large unknown continent labeled Terra Australis Incognita, a speculative landmass believed necessary to “balance” the globe.

Despite these inaccuracies, Ptolemy’s rendering of the world was, in many ways, more systematic and comprehensive than anything that had come before.

His work reflected a worldview bounded not by myth, but by measurement. Mountains, rivers, cities, coastlines—all were presented in a manner intended to be reproducible and logically structured, even when based on flawed data.

He shifted the focus from story to structure, from hearsay to hypothesis.

In retrospect, the world according to Ptolemy appears both remarkably advanced and charmingly naïve.

It combined deep analytical thinking with the limitations of the information available in the second century. But what’s most compelling is how his worldview, as flawed as it was, set the stage for discovery.

Ptolemy’s Influence on Later Cartography

Though Ptolemy composed Geographia in the 2nd century CE, its true influence would not reach full bloom until more than a millennium later.

After its initial creation and use in the Roman and Byzantine worlds, the text gradually faded into obscurity in Western Europe during the early Middle Ages.

But Ptolemy’s work was not lost—it was preserved in the Byzantine Empire and later rediscovered, translated, and disseminated during the European Renaissance, igniting a revolution in cartography that would forever alter how humans perceived the planet.

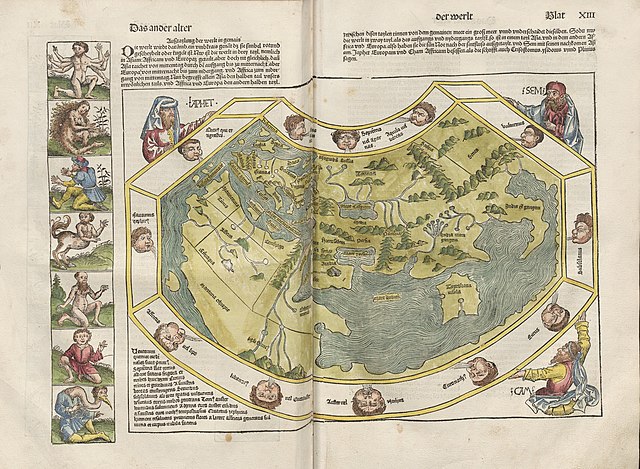

During the medieval period in Western Europe, geography was deeply shaped by religious doctrine and classical cosmology.

Most maps of the time—such as the symbolic T-O maps—were not designed for navigation or scientific inquiry but for illustrating theological principles. Jerusalem was often placed at the center of the world, and knowledge of far-off lands was mixed with myth and allegory.

In contrast, the Islamic world preserved and expanded upon Greek scientific knowledge, including works by Ptolemy.

Arab scholars translated and commented on Geographia, integrating it with their own geographic and astronomical advancements. Figures like al-Idrisi, al-Biruni, and others played a crucial role in keeping geographic science alive during the so-called "Dark Ages" of Europe.

The turning point came in the 13th and 14th centuries, when Byzantine scholars began reintroducing classical Greek knowledge to the Latin-speaking world.

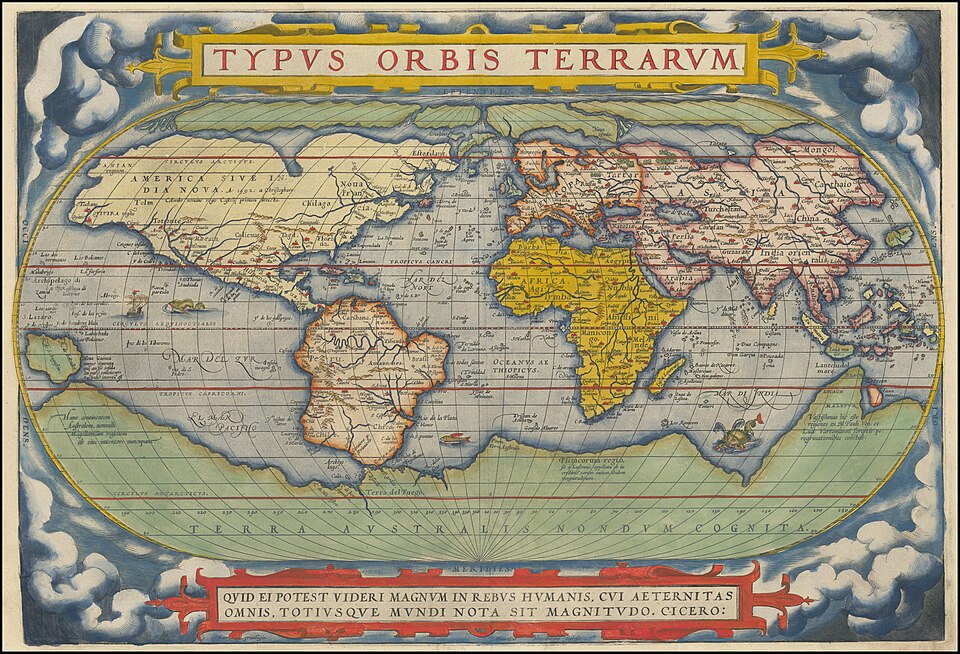

In 1406, a Greek manuscript of Geographia was translated into Latin by the Florentine scholar Jacopo d’Angelo. This translation became the basis for printed editions that circulated widely in Europe, beginning with the first printed edition of Geographia in 1477 in Bologna.

This edition included maps that were reconstructed based on Ptolemy’s coordinates, offering Renaissance Europe its first glimpse of a mathematically conceived, coordinate-based atlas.

Ptolemy’s rediscovered work aligned perfectly with the humanist ideals of the Renaissance, which celebrated classical knowledge and emphasized empirical observation and systematic inquiry.

His methods offered a scientific alternative to the religious symbolism that had long dominated mapmaking. Renaissance scholars and artists, including Leonardo da Vinci and Gerardus Mercator, were inspired by Ptolemy’s insistence on structure and precision.

Ptolemy’s methods also paved the way for the systematic collection and classification of geographic data. As European powers began to explore and colonize distant parts of the world, they used maps not only for navigation but for political and economic domination.

The scientific tone of Ptolemy’s work gave cartography a veneer of authority—maps became tools of empire, charting claims and territories with the implicit trust of mathematics behind them.

By the 17th century, the world had changed dramatically. Continents unknown to Ptolemy had been “discovered,” trade routes spanned the oceans, and the Earth’s circumference had been measured with far greater accuracy.

Still, Geographia remained a foundational text in the history of geography and was widely studied well into the Enlightenment. Even as his mistakes were corrected and his worldview eclipsed, Ptolemy’s emphasis on coordinates, projections, and reproducibility lived on.

In essence, Ptolemy was the bridge between the ancient and modern worlds of cartography.

His influence is visible not only in the maps that guided early explorers but also in the very structure of today’s geographic thought.

From globes and atlases to satellite imagery and digital mapping, the seeds planted by Geographia continue to shape how we navigate and understand our world.

From Geographia to GPS: Final Thoughts

Claudius Ptolemy’s Geographia stands as a testament to the enduring power of knowledge, imagination, and systematic inquiry. Composed nearly two thousand years ago, this groundbreaking work transformed how people conceived of the world—and of their place in it.

Ptolemy did not discover new lands, nor did he travel the globe. Instead, he explored the boundaries of human understanding using the tools of his time—observation, logic, and mathematics.

Despite his many errors—the miscalculated circumference of the Earth, the enclosed Indian Ocean, and the exaggerated size of Asia, to name a few—Ptolemy’s influence was more constructive than limiting.

His mistakes, framed within a structured system, invited correction and refinement. They gave future generations a solid foundation on which to test new hypotheses, incorporate new discoveries, and eventually chart the Earth with increasing accuracy.

What makes Geographia so remarkable is its timeless ambition.

Ptolemy envisioned a world that could be known, mapped, and understood through reason and measurement. That idea alone was revolutionary in a time when many maps were as much expressions of mythology, religion, and political power as they were representations of physical space.

Ptolemy’s insistence on reproducibility, standardization, and precision foreshadowed the empirical ideals that would come to define the scientific revolution more than a millennium later.

Even in the modern era of GPS satellites and real-time digital cartography, the legacy of Ptolemy endures.

The very idea of using a grid system to locate places, of employing projections to translate a globe onto a flat surface, and of quantifying spatial relationships across vast distances—all trace their roots back to Ptolemy’s vision.

Today’s global infrastructure, from air traffic navigation to climate modeling, is built on principles he first proposed nearly two millennia ago.

Ptolemy's Geographia was not a static artifact. It was a living document that evolved with its readers, inviting reinterpretation and revision as human knowledge expanded. And while his maps may not have charted every coastline or correctly scaled every landmass, they charted something arguably more important: humanity's enduring desire to understand its place on Earth.